Escaping the planning mismatch

Breaking the service paradox

Going on a family holiday entails a whole host of decisions. Some are made early on in the process, such as the period of time, destination and means of transport, and others much later, such as when and where to stop to eat, to refuel and to go to the toilet. There is a clear reason why you make the latter decision late on in the process: bladders are notoriously unpredictable! Scheduling comfort breaks in advance is asking for trouble in the form of wet pants or – to avoid that risk – a compulsory stop at every service station along the way, so it’s not to be recommended. What seems so obvious in everyday life, however, often goes horribly wrong for businesses.

It is not hard to become better yet more expensive, or to offer lower prices but also lower quality. Things only become difficult when you face the challenge of becoming better and cheaper at the same time. As a result, many companies have been grappling with this seemingly insurmountable situation known as the ‘service paradox’ for years. More recently, however, a small but growing number of companies have managed to break this paradox, and their secret is surprisingly straightforward. They simply refuse to accept their dependence on chronically unreliable forecasts and plans any longer. Instead, by eliminating unnecessary variation and uncertainty and by advancing riskless decisions, they have been able to delay risky decisions in order to successfully escape the ‘planning mismatch’.

Essential alignment

In order to break the service paradox, alignment is essential – both internally and throughout the supply chain. After all, in order to become both better and cheaper, everyone everywhere must always do the right thing and make the right decisions – not in their own local interests, but for the good of the whole. That means taking an integral chain-based approach to supplying what the end customer wants, when they want it and without waste: demand-driven alignment.

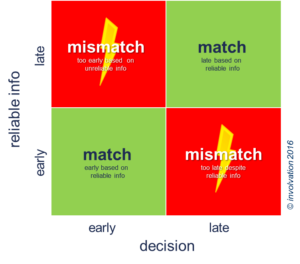

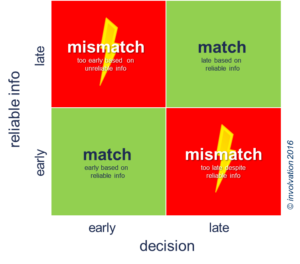

Of course, the million-dollar question is how to achieve demand-driven alignment. Needless to say, carefully formulated targets and key performance indicators (KPIs) play an important role in that. Effective targets and KPIs stimulate the desired behaviour and right decisions, and discourage undesired behaviour and wrong decisions. In practice, however, this is not quite so easy. After all, it is not uncommon for targets and KPIs to be beyond your scope of influence, especially externally. Luckily, there is another factor that you can influence, namely the ‘moment of decision’. That is the precise point in time that you make a particular choice. This can be ‘early’, i.e. a long time before the decision must take effect, or ‘late’, e.g. at the last minute. Preferably, the moment of decision should be early if the information is reliable at an early stage, and late if it doesn’t become reliable until later. This is not always the case in practice, however, which creates a ‘planning mismatch’.

The decision matrix

Decisions can be placed in a matrix, with the early or late availability of reliable information along the vertical axis and the early or late moment of decision along the horizontal axis. This decision matrix shows that there are two variants of the planning mismatch: the first in which decisions are made too early (while the information is still unreliable), and the second in which decisions are made too late (when the available information is not utilized, thus causing unnecessary delays in decision-making).

In the first variant of the planning mismatch, decision-makers will understandably often be motivated by self-interest and attempt to mitigate their own risks first. For example, when attempting to be efficient and reliable in the face of variable demand and unreliable forecasts, a production manager will tend to issue longer lead times and plan the capacity conservatively. Meanwhile, to avoid shortfalls, Sales will exaggerate the forecast slightly, and an inventory planner will tend to reorder a little sooner and a little more than necessary.

Moreover, in the case of stock-driven supply chains, the presence of uncertainty and long lead times serves as a catalyst for even more variation and uncertainty upstream. After all, the combination of uncertainty and long lead times is the primary source of the renowned bullwhip effect.

Some common examples of early decisions include a manufacturer who has to plan his capacity and an inventory planner who has to place orders based on an unreliable forecast. All in all, the first variant of the planning mismatch is a far-from-ideal situation in which alignment is nowhere to be seen. Plans have changed before the ink is even dry, and ad-hoc remedies are almost standard practice rather than an exception. The consequences are obvious: long and unreliable lead times despite high costs, and/or out-of-stock situations despite high inventory levels, a whole load of hassle and – not unusually – finger-pointing and mutual distrust.

Early certainty

In the second variant of the planning mismatch the decision-makers themselves fail to utilize reliable information that is available at an early stage in order to make early, ‘riskless’ decisions. Some examples of the second variant include failure to provide suppliers with early volume certainty by providing purchase guarantees and, in the case of dependency on a particular production sequence, failure to formalize the production schedule in advance using so-called ‘rhythm wheels’.

The second variant of the planning mismatch is far from ideal either. It is of course a great shame to fail to capitalize on the efficiency potential of early riskless decisions, such as the rhythm wheel mentioned above, for example. However, this becomes even more regrettable when one considers that an early riskless decision could potentially give other partners sufficient early certainty to make the right decision, such as in the above-mentioned purchase guarantees. Hence, making decisions too late – or, to put it more accurately, failure to decide early and provide certainty – by one partner can result in another partner having to decide too early. So the second variant of the planning mismatch appears to cause the first one!

In other words, the planning mismatch is a recipe for disappointment and disaster, and a source of misalignment. If companies want to break the service paradox, they will have to escape the planning mismatch.

Three DDSCM strategies

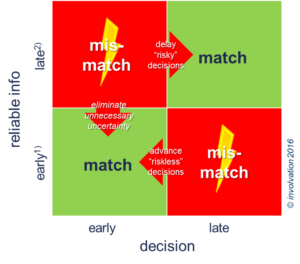

The question is, how can companies escape the planning mismatch? As it turns out, the answer is surprisingly simple. After all, the decision matrix reveals three complementary strategies for escaping the planning mismatch. First of all, companies must delay risky decisions until sufficient reliable information is available. Secondly, they must make use of information that is available at an early stage in order to bring forward riskless decisions. And lastly they must eliminate unnecessary variation and uncertainty.

Incidentally, these three strategies not only complement one another but are also interlinked. After all, delaying risky decisions calls for short response times. This requires certainty, which can be gained by advancing riskless decisions. But to do so, it is important to eliminate unnecessary uncertainty, which in turn means eliminating unnecessary variation. After all, variation is what causes uncertainty. If these three strategies are applied correctly, they actually reinforce one another.

This train of thought reveals that, by eliminating unnecessary variation and uncertainty and by bringing forward riskless decisions, companies can delay risky decisions in order to successfully escape the planning mismatch and reduce their dependence on chronically unreliable forecasts and plans. This safeguards alignment and gives the end customer what they want, when they want it and without waste: a win-win situation which breaks the service paradox, i.e. a customer-driven supply chain.

Hence, demand-driven supply chain management (DDSCM) is a collection of supply-chain initiatives that enable companies to escape the planning mismatch and to lessen their reliance on forecasting by improving agility and response times, thanks to eliminating unnecessary variation and uncertainty and advancing riskless decisions.

Opting for DDSCM implies that a company no longer accepts its dependence on chronically unreliable forecasts and plans caused by long response times and unnecessary variation and uncertainty. The ‘demand-driven’ aspect stems from the fact that, in the extreme case, risky decisions are delayed until the actual demand level is known and that forecasts are based on the need at source so as not to be distorted by self-inflicted variation.

Wheel of Five for DDSCM

A company must apply five complementary principles to develop a demand-driven supply chain. Firstly, eliminate unnecessary variation in supply and demand. Then absorb unpredictable variation with stock and time, and chase predictable variation with potential flexibility and effective decision-making. Avoid overload by controlling the workload and keeping spare capacity at strategic locations. Last but not least, eliminate waste of capacity, stock and time.

Together, the five guidelines in this ‘Wheel of Five’ for DDSCM are aimed at reducing response times while also eliminating unnecessary variation and uncertainty in order to escape the planning mismatch. On the one hand, the principles are designed to inspire companies to devise their own demand-driven improvement strategies and solutions, and on the other companies can use them to check whether their improvement measures will actually help them to escape the planning mismatch.

By the way, when applying these five principles it is essential to differentiate between ‘necessary’ and ‘unnecessary’, or ‘good’ and ‘bad’. To make this distinction, companies need to determine what their end customer really needs and when. ‘Necessary’ and ‘good’ are variation and buffers that make a positive contribution to that. Anything that does not should be classified as ‘unnecessary’, ‘bad’ and ‘waste’.

Amazing results

Thankfully, we are gradually seeing more and more companies that are no longer willing to accept their dependence on unreliable forecasts and plans. Having realized the limitations of forecasts and plans, especially when it comes to predicting future details, they have opted for some form of DDSCM. The results have been amazing for all of them: better and cheaper with less hassle. In addition to international cases such as Zara and Apple, companies closer to home such as Auping, Picnic, Shell, Enexis, Stedin and Liander have all enjoyed success. For example, with its guaranteed short delivery times, bed manufacturer Auping is a positive exception in an industry that is traditionally known for its long and unreliable lead times. Because Auping produces its beds in line with customer-specific orders, make to stock is not an option. Instead, Auping has transformed its factory from a classic ‘job shop’ to a ‘flow shop’. By controlling the workload in combination with the resulting shorter lead times, the company has managed to become both efficient and responsive.

The growing awareness of DDSCM is also increasing the focus on demand-driven planning concepts, ranging from Repetitive Flexible Scheduling to Scrum and from Drum Buffer Rope to POLCA. Perhaps the most notable approach is DDMRP, which has even been embraced by SAP recently. Although they are all different because they have been developed for use in different situations, what they all have in common is that they are in some way based on demand-driven principles.

Over the coming decade, the number of companies actively attempting to escape the planning mismatch – whether they call it DDSCM or not – will undoubtedly skyrocket. Companies that choose to ignore DDSCM will remain at the mercy of the planning mismatch, placing their financial performance in the hands of unreliable forecasts and plans.